Before beginning a startup, it is wise to think twice. The rate of failed startups is very high. But that high percentage can also be viewed in a positive light. It means that there is much to learn from other people’s mistakes. A new business owner is likely to make mistakes and that is ok. But it is not necessary to make the same mistakes that led to the downfall of other startups.

Not every failed startup is a failure. That sounds like a contradiction. But even a failed startup contributed in some way. Some made innovations in certain areas that benefited other people or companies. Other failed startups were able to return some money to their investors.

What are the reasons then that so many startups do not blossom into stable full-grown companies? Finding out what the real reasons are in each case is not easy. Still, analyzing afterward what happened and reading the related reports can be very insightful.

This article looks at 27 examples of famous startup companies and analyzes the reasons for their failure.

Failed startups examples

Quibi

We’re going to start the failed startups list with one big oops that bit the dust lately. Quibi was founded and led by a group of knowledgeable and experienced executives. They raised a staggering $1.75 billion. Their product, short-form, serialized video content, failed to attract a large audience. All that, despite the lavish, large productions they put out.

Some of the United States’ leading business people were at the helm of Quibi. Quibi launched their app in April 2020, right at the beginning of the Corona pandemic. It was to cost $5 monthly or $8 per month without ads.

At the time of the premiere, the U.S. and many other countries had entered lockdown for health reasons. But that was not the root cause for Quibi’s failure. From the beginning, the project was doomed to fail. Still, many large media companies had invested money in Quibi.

Quirky

The next startup failure we present in this article is Quirky. The company intended to be a platform where professionals could meet to develop needed ideas. It started in 2009 and soon collected $169.5 million in capital. Besides the money, they earned a partnership with GE. On top of that, CNN featured Quirky in 2012.

But in 2015 the company could not continue by itself and sold for $4.7 million. That Quirky at first failed, was due to the business model and a product that performed poorly. By bringing out too many products in a short time, the revenues were too low. The quality of the products was mediocre and they were difficult to manufacture.

Want to give your startup a chance? Check out this course from Wharton University.

You’ll take the Entrepreneurship 2 course if you want to learn practical skills and gain comprehensive knowledge about creating a successful start-up.

You’ll learn about lean approaches, minimum viable products, team management, legal aspects, and more to help you launch and grow your business, and be prepared for the next level in Entrepreneurship 3.

Layer

The total funding amount for Layer Inc. was $44 million. The company’s objective was to develop an open cloud service for the communication sector. The idea was to use VoIP (Voice over Internet Protocol) to create a flexible, expandable service network. The idea and technology behind the idea were solid and had great potential.

Despite the innovative idea and sound funding, Layer closed its doors in October 2019. The communication industry in the 2010s was very competitive and Layer Inc. was not able to compete with its rivals.

Initially, the company grew very fast. The investors wanted quick money and pressured Layer to grow faster. The competition consisted of large established companies like Intercom. The final product was not as reliable as hoped and did not compare with the other products on the market.

ScaleFactor

ScaleFactor was an accounting and finance software platform. It had the backing of $100 million from different investors. The promise it made to its customers was that it would automate all their bookkeeping needs.

In a Forbes interview, CEO Kurt Rathmann blamed the COVID-19 pandemic for the failure. This sounds like a plausible explanation. However, ScaleFactor was in trouble at an early stage, long before the pandemic appeared.

In the technology business, it is common practice to claim that business is going well, even if this is not true. The capital investment firms behind these startups encourage this pretense. The tech industry is extremely lucrative. It is possible that, in time, large investments would see a return.

The problem with ScaleFactor was that its focus was on costly marketing strategies. The development of a product that met the needs and expectations of customers was not a concern. Various former employees confirmed that this was the case. When customer numbers began dwindling, executives attempted to cover up the problem.

Homejoy

Homejoy was a platform that, at a fixed rate, connected independent professional cleaners with clients.

This plan started with funding of $38 million in 2013. The expectation was that this large investment would see a return in time. You might think this is a product market fit issue, but it’s not.

After its start, Homejoy grew fast. Within half a year, it had branches in 30 cities. To attract customers, the services were offered at a discounted rate. This made the growth stage expensive.

Three problems led to the downfall of Homejoy. The first problem was the costly promotional offers during the initial growing phase. Secondly, the expansion was too forced. The rapid growth did not help the company to stabilize. And finally, the independent cleaning contractors did not receive the needed training.

Yik Yak

YikYak’s start was very promising but as you might have guessed by now, it didn’t do well since it’s on our list of startup failures.

It offered an anonymous message posting platform aimed at the local community. It became very popular at college and university campuses nationwide. Starting with a capital of $74 million, Yik Yak’s value soon grew to an estimated $400 million. Not long after this, Square purchased Yik Yak for about $1 million. Snapchat also launched its app and gained a large part of the market.

With millions of users, it had great potential to bring in a lot of money. The strategy was to do that by taking away the thing that made it so popular in the first place, anonymity. In essence, they wanted to turn it into a platform similar to Facebook and force users to make a profile.

After that things got worse. Due to cyberbullying, threats, and other inappropriate content, many campuses banned the app. The app never offered a group chat feature. On top of this, Yik Yak was not consistent in publishing engaging content.

Beepi

On paper, the idea behind Beepi looked encouraging. Beepi wanted to become a P2P platform for buying and selling used cars. Beepi started at a time when this kind of online marketplace had great potential. At startup, Beepi was able to raise $60 million in a Series B funding round.

In 2017 Beepi decided to close its doors. It had been in business for more than four years. At first, used car dealer DGDG was one of the candidates to take over Beepi, but the negotiations failed.

Beepi is a classic example of a good idea that failed because it was poorly executed. The company wanted to grow too fast and spendings were not realistic. At some point, the company spent about $7 million a month in salaries alone, of which top executives took a large part. This careless spending led to the demise of Beepi.

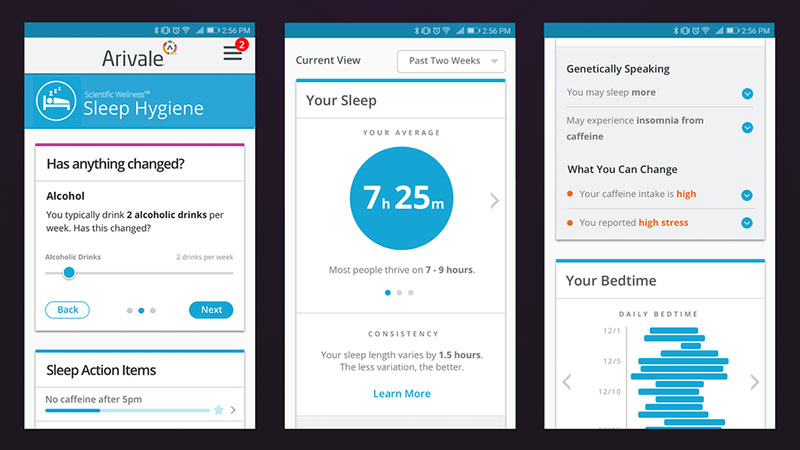

Arivale

Arivale was a revolutionary idea that ultimately ended up being a failed startup. It pioneered the field of scientific wellness. Genetic testing was used for personal coaching to benefit the client’s health. With an employee count of about 120 people, it collected $52.5 million. At its peak, it boasted some 5000 customers.

After four years, Arivale suddenly announced its closure, much to the surprise of the customers and employees.

The problem behind the failure was that the cost of the service was far higher than the price of the service. At the time that Arivale started, the technology was still in its infancy. Much research was still needed to lower the cost of the procedure. All the time that the company was operational, it was running at a loss.

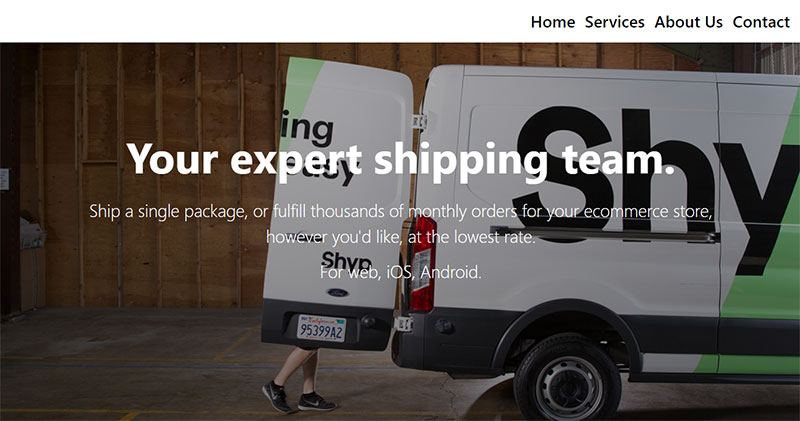

Shyp

Shyp was a VC backed shipping company, as the name might give it away. They claimed that contracting their services was as simple as two taps on a smartphone. This line attracted the attention of the New York Times, who covered an article about Shyp. This in turn attracted the interest of some large investors. Shyp raised $62.1 million.

The slowdown in the number of customers led to the collapse of Shyp. As a result, the company grew faster than the number of shipments. Although aware of the problem, the company failed to adjust its course. The mentality to grow at all costs is what led to Shyp’s going down.

Anki

Established in 2010, Anki was a robotics and artificial intelligence startup. It aimed to combine robotics and the Internet of Things (IoT) into children’s toys and games. This would result in programmed toys that could intelligently adapt to the environment. Besides that, it would make a considerable contribution to the field of AI and robotics.

Anki failed to celebrate its tenth anniversary and closed in April 2019. Quite surprising, considering that some of the smartest brains were working there. They had also obtained $182 million in venture capital.

The Anki products themselves were of good quality and were performing well in the market. Competitors were unable to produce anything similar. This being the case, the $300 price tag was very modest.

According to the long-term prognosis, Anki would never have survived. Even though it sold more than 1,500,000 units, it was not enough to keep the organization running for another year.

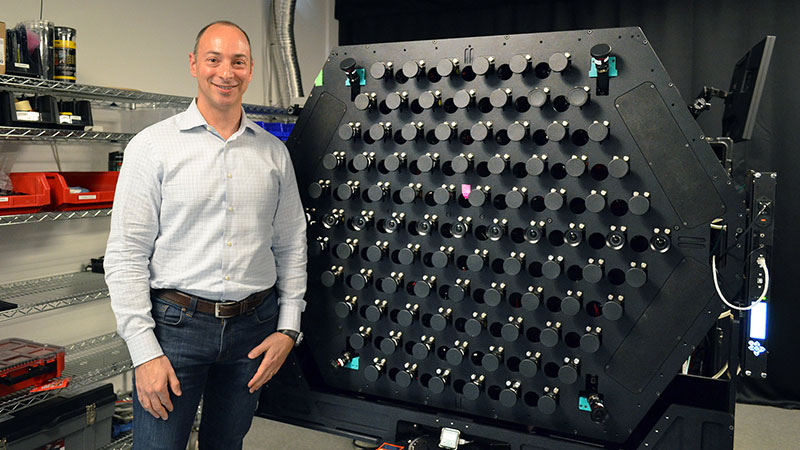

Lytro

Lytro collected a total amount of $215.8 million in funding. The technology company developed a camera that was able to refocus images after capture. The depth and light-field technology behind image enhancement were later used in virtual reality.

The Light Field imaging technology never gained popularity with photographers. So Lytro changed its focus to virtual reality. The goal was to engage large production studios to fund the Immerge camera project.

The products that Lytro brought to market were not of the standard that they promised. Reviews stated that the image quality was very poor and that the product was useless for professional photographers. The main reason for the downfall of Lytro was the failure to recognize the need for a good quality product.

Hollar

Hollar was an online dollar store that launched in 2015. As venture capital, they raised more than $75 million. Some five years later Hollar announced the closure of the shop due to financial problems.

Hollar made it known that it was looking for a buyer. Five Below acquired it and took over some of the employees and other assets. By selling many articles at a time, Hollar was hoping to reduce shipping costs. Yet, those hopes never came true, causing the shop to never break even.

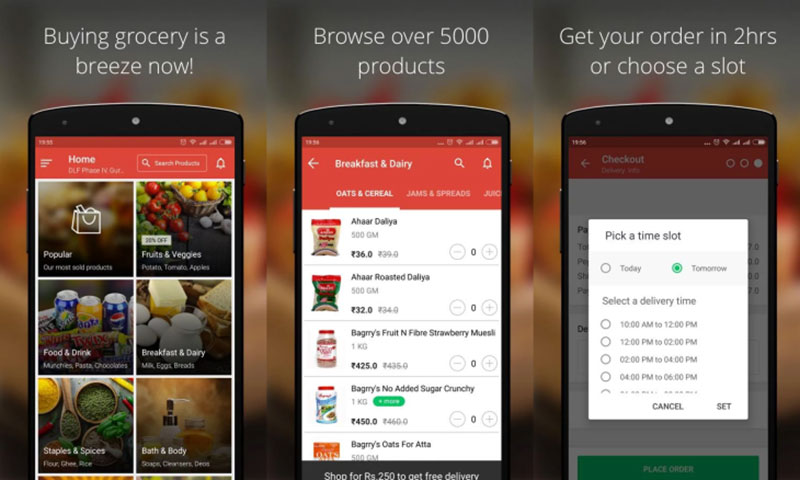

Peppertap

Peppertap is another one of these startup failures. Unlike others that are established in Silicon Valley, this one was an Indian company based in Gurgaon. Backed by $51.2 million, it set up a grocery delivery service in 2014. To revolutionize grocery shopping at the lowest cost, it partnered with many local shops. The result was rapid geographic expansion.

There are also some drawbacks to their approach. For this idea to work, it requires seamless integration of the local shops with the mobile app. This was not the case. To attract many customers, and to keep them, Peppertap offered large discounts. Although this built customer loyalty, Peppertap lost money on every order. Thus, the funds ran out.

Jawbone

In this list, Jawbone is one of the biggest failed startups. This electronics company gathered $930 million in venture capital. Jawbone produced Bluetooth speakers, headsets, fitness trackers, and so on.

Cracks in the company’s success started to appear in 2016. This was when they stopped producing and selling their fitness trackers. In the end, they had to sell the remaining stock to a reseller.

Experts say that it was overfunding that led to the company’s demise. It caused the values of the company to appear higher and more stable than it was in reality. It must also be noted that Jawbone’s products did not meet the standards of the competition.

Exec

This house cleaning service offered their services by iPhone or internet. Apart from cleaning, the employees would do any kind of errand. In the first fundraising round, Exec obtained $3.3 million. In the end, Handy bought it for $10 million.

According to the company’s executives, only 30% was spent on overhead costs. The main cost was the salaries of software engineers. Of the $25 per hour, 80% went to the errand-runner. The remaining 20% kept the company running.

But mistakes made by employees and refunds made to customers quickly consumed the profits. If you too have large costs with your software engineers, check out what we can do, and maybe we can help you get your software development costs at a reasonable level.

Videology

Created by Scott Ferber, Videology had a total funding of $201 million. He started the company in 2007. The goal was to get advertisers to place ads on digital platforms to reach their target audience. It also offered the tools to measure the video’s efficiency.

Videology is an example of an idea that was too far ahead of its time. The industry at the time was not able to incorporate the ideas. Videology in turn was not able to adapt to the industry and ended up a startup failure.

Another problem relates to Google and Facebook changing their advertising policies. They no longer allowed outside companies to buy ads. All advertisements had to be purchased from Google.

Sorabel

Sorabel was an Indonesian fashion e-commerce startup. At the beginning of 2019 growth seemed to be steady. The future looked very bright and the prognostics were that it would be profitable. Yet, Sorabel is now in administration and seeking a new investor.

The Covid-19 pandemic ended the company’s Series C round of fundraising all of a sudden. At that moment negotiations with a Chinese investor were in their final stages. The interruption of the negotiations cost Sorabel some $30 million.

Sorabel never had a large amount of money on hand, never more than six months’ worth. The lack of this cushion turned out to be fatal. When the pandemic hit it was not able to move as swiftly as other similar shops. Zilingo, for example, began selling personal protective gear after the outbreak.

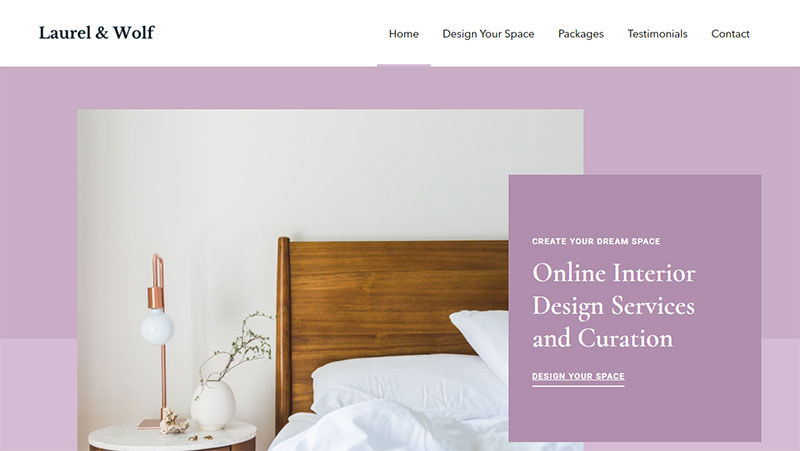

Laurel & Wolf

Laurel & Wolf is an online design marketplace. Backed by $35.8 million in funding, its goal is to make professional interior design available and accessible.

Laurel & Wolf has always presented itself in a positive and marketable way. But by the summer of 2018 more and more negative reviews started to appear on the internet. Generally, the complaint was that products arrived damaged, or not at all. Because of unfavorable attention, a large number of designers left the platform. Many other Laurel & Wolf employees were also dissatisfied with the company.

The bottom line is that Laurel & Wolf ventured into a business that was new to the internet. They may have been ill-prepared for difficulties with employees and the operational costs.

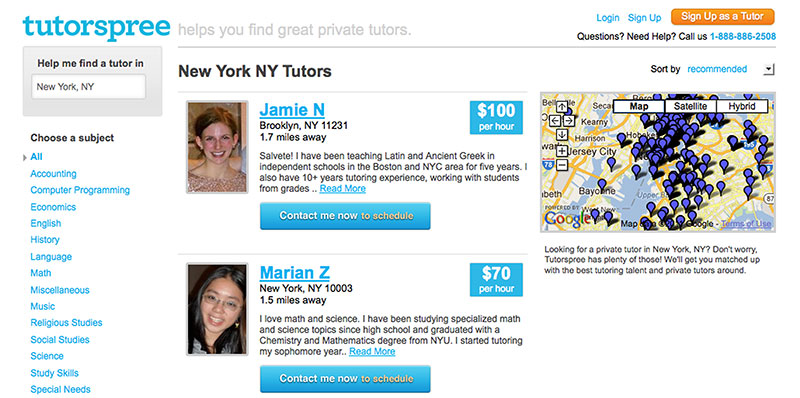

Tutorspree

Tutorspree nicknamed itself the “Airbnb for tutors”. It received funding from Y Combinator in 2011 to get started. In total it received $1.8 million from various large investors.

The Tutorspree founders had limited experience in the education industry. And they hardly allowed themselves time to get acquainted. The tutoring market is complicated and very competitive. Complications include seasonality and geographic limitations. After the tutor and student establish contact, it is very easy to bypass the intermediary and avoid paying fees.

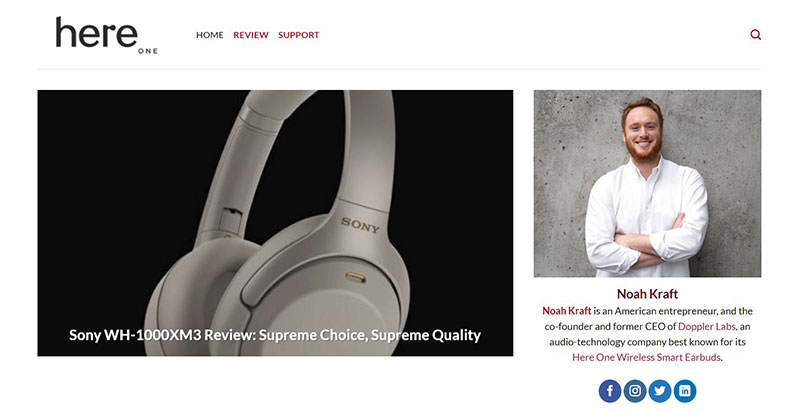

Doppler Labs

Doppler Labs’ major product was ‘Here One’. Here Ones are wireless earphones with built-in microphones. In the beginning, Doppler Labs expected to sell 100,000 Here Ones. They were able to gather $51.1 million to launch the product. In the end, they only sold a disappointing 25,000 earphones.

The earphones were new and had some outstanding features that made them unique. Somehow, Doppler Labs failed to bring those features to the attention of the customers. Besides the marketing issues, the product showed some technical issues. Due to release delays, Doppler Labs missed out on the crucial holiday season sales.

In the meantime, the competition released the AirPods, which had a battery life of five hours. Here Ones only lasted two.

Vicis

The Vicis football helmet company started in 2014. It came about as a spinoff from research performed at the University of Washington. A team of experts, ranging from engineers to medical experts, designed a special helmet. This helmet consisted of various special layers that would mitigate the impact. The helmet was able to lower the chance of concussions.

To finance the company’s startup more than 400 investors contributed a total of $85 million. According to the New York Times, Vicis failed to gain a market share in the competitive sports gear market.

The focus of attention was on stealing market share from others. The skewed focus took attention away from Vicis making a profit in its own strength. Vicis was not able to take customers away from established helmet producers.

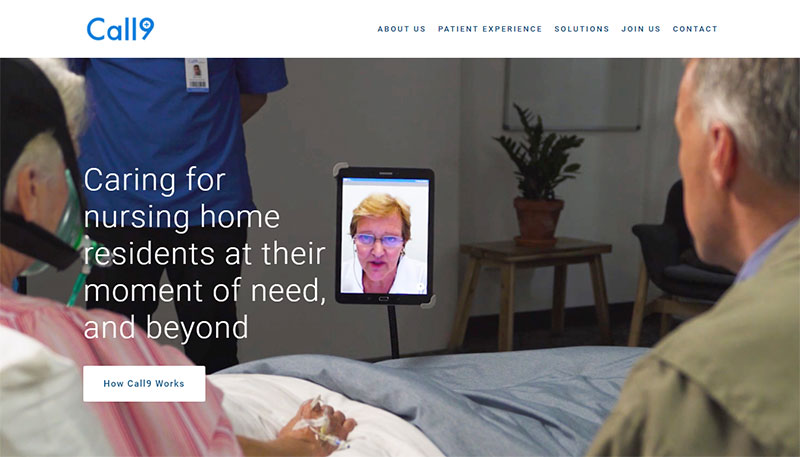

Call9

Call9 provided medical equipment and help by video chat for nursing home residents. It managed to raise $34 million as startup capital. This amount was insufficient to expand the business and cover the high costs of running a health-care business.

Call9 provided professional medical advice through their app. Using different platforms, Call9 doctors could assist local nurses. In this way, unnecessary and costly emergency room visits could be prevented.

According to insiders, there was a problem between the company’s executives and the biggest investors. The lack of funding led to the downfall of Call9.

99Dresses

The 99Dresses founder noticed that high-end designer clothing items were often hardly worn and then left in the closet. She decided to develop a virtual closet app. The app offered secondhand and inter-trade items.

99Dresses was a platform for trading fashion items between users. The company made money by charging a value-based fee on every transaction. As venture capital, it raised $105,700.

Despite the good intentions of the founder, 18-year-old Nikki, 99Dresses’ business model was not successful. Nikki had no experience and no background in the tech business. For one year she managed to cover the weaknesses. But then technical and financial problems led to the shutting down of the website in 2014. In conclusion, the website did not bring in enough money to keep the business going.

This isn’t a big crash like the other failed startups that you’ve seen so far, but it’s one that is more grounded and close to what the majority of new entrepreneurs would try.

Rethink Robotics

Rethink Robotics worked to improve robotics in the production environment. The company started to develop their own previous work, Baxter and Sawyer. These had been launched in 2011 and 2015 respectively. The amount collected for this spinoff was $150 million.

The first problem was the product itself (product market fit issue). Rethink was not able to adapt Sawyer or Baxter to the needs of the production market. It did find some application in education, training, and research. Now, the robotics market is entering the era of robotics (cooperative robotics).

Rethink was not able to make it through the first years of its existence and establish itself. On top of that, the company was not able to find a large investor to take over the business.

Cherry

Cherry was a car wash service. Customers could park their car anywhere and request the service online. Cherry received $5.25 million in funding.

Cherry was not able to attract enough bookings, though. This would be very difficult because car owners only need a limited number of car washes a month. The only way for Cherry to survive would have been to attract more customers. Or they could have offered other automobile-related services or products. Either way, their business model didn’t work.

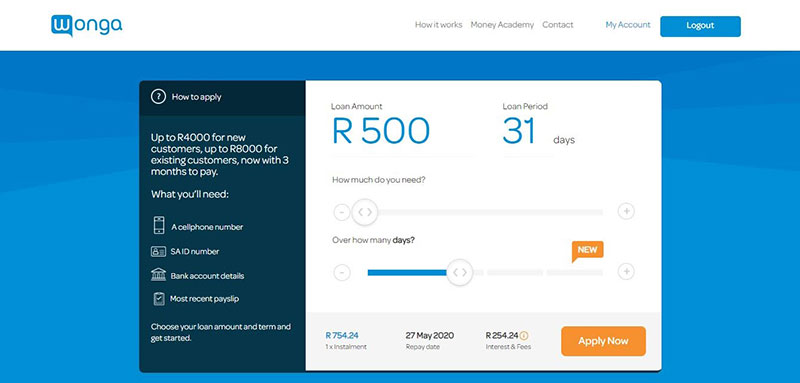

Wonga

Wonga was a British company that offered short-term loans. This is a classic example of the rise and demise of a startup. It had an interesting idea and there were enough investors to support it. At the end of the month, many people are a little short on cash. So Wonga offered small loans, at high interest, to help customers make it to the next payday.

It is little surprise that most borrowers had difficulties paying back their loans. This brought the credit provider into big trouble. Stories started to appear in the media that many Wonga customers could not pay off their loans. As a result, the authorities became more strict in regulating the company’s activities.

Besides the government actions, Wonga had to pay out large amounts in compensation. In the end, £10 million was injected to keep Wonga afloat.

Aria Insights

The last one in this failed startups list is CyPhy. The total funding amount was $39 million.

CyPhy was an American drone company. Later they changed their name to Aria Insights and started to develop specialized and advanced drones. Their most famous plane was the PARC (Persistent Aerial Reconnaissance and Communication). Its most interesting feature was its long flight time. It was able to stay in the air for days, instead of hours.

The reasons that it failed are many and complicated. A major factor was the departure of founder Helen Greiner. A change in leadership affects the direction and continuity of a company. The risk is also that new management only comes in to fill their pockets and leave again.

Likely, that was not the sole reason. Another reason could be the change of focus from drones to AI systems.

FAQs about failed startups

1. What are some of the most common reasons why startups fail?

Several factors might cause a startup to fail, including a lack of consumer demand, inadequate capital, poor management, an inability to keep up with market developments, and intense competition.

2. How can a founder identify when their startup is likely to fail, and what steps can they take to turn things around?

Warning indicators include diminishing revenue, low morale, and a high personnel turnover rate should be taken note of by founders.

Founders can analyze their strategy, make any necessary adjustments, seek mentorship or consulting, and concentrate on assembling a talented staff to turn things around.

3. What are the biggest mistakes that founders make when starting a new company?

The biggest errors include failing to conduct sufficient market research, underestimating the significance of cash flow, attempting to handle everything on your own, and forgoing input from mentors and consumers.

4. What role do investors play in the success or failure of a startup, and how can founders mitigate the risks associated with investment?

For entrepreneurs, investors can offer crucial capital, knowledge, and networking possibilities. Yet, founders must be cognizant of the dangers of ceding ownership and must only collaborate with respectable investors who share their objectives and principles.

5. What are the key factors that distinguish successful startups from those that fail?

Clear value propositions, strong market fit, dependable teams, cutting-edge goods and services, and successful strategy execution are characteristics of successful companies. Moreover, tenacious, flexible, and growth-minded individuals make for successful founders.

6. What is the impact of competition on the success or failure of a startup, and how can founders respond to competition effectively?

For startups, competition may be a double-edged sword because it can both help validate the market and encourage innovation while also eroding market share and profitability. Entrepreneurs should concentrate on standing out from rivals, building a solid brand and clientele, and consistently innovating.

7. How can founders stay motivated and focused when facing setbacks and failures in their startup journey?

Founders can maintain motivation by concentrating on their objective, asking for help from peers and mentors, taking care of themselves, and viewing failures as opportunities for improvement.

8. How can a founder ensure that their startup has a strong product-market fit, and what are the consequences of not achieving this fit?

By conducting market research, asking for feedback from potential clients, and refining their product or service in response to that feedback, founders can guarantee product-market fit. Low sales and eventual startup failure can be the results of failing to create product-market fit.

9. What can founders do to prevent burnout and maintain a healthy work-life balance while trying to launch and grow a startup?

By establishing limits, assigning duties, prioritizing self-care, and enlisting the aid of peers, mentors, and coaches, founders can avoid burnout. A healthy work-life balance can also be attained by developing a strong team and a great workplace culture.

10. How can founders effectively manage and communicate with their team during times of failure and uncertainty?

By being open about the company’s prospects and difficulties, involving staff in problem-solving, giving clear communication and feedback, and establishing a culture of trust, collaboration, and resilience, founders may effectively manage their team.

Ending thoughts on these failed startups

The success of a startup is not guaranteed by having venture-backed money on your hands. The business world is changing all the time. So any company that is unable to keep up with these changes will likely fail. It does not make a difference if it has large investments behind it.

Many former market leaders came to an end because they were unwilling or unable to innovate and change. Reading and understanding the market is as important as having financial support. Everyone is aware that 2020 has been a difficult year for businesses. Hopefully, 2021 will present more opportunities for startups to bring new products and services to the market.

This article showed many examples of startup companies that failed. By learning from these failures, new businesses can avoid making the same mistakes. They gain valuable insights and are ready to adapt when necessary.

If you liked this article about failed startups, you should check out this article about what happened to MoviePass.

There are also similar articles discussing what happened to Quiznos, what happened to Pan Am, what happened to Sears, and what happened to BlackBerry.

And let’s not forget about articles on what happened to Pontiac, what happened to Circuit City, what happened to American Apparel, and startup failure.

We also wrote about a few related subjects like financial projections for startups, startup consultants, startup advice, startup press kit examples, Berlin startups, types of investors, share options, London startups, gifting shares, best startup books, and risk management process.

- Preventing Emails From Going To Spam In Gmail with GlockApps - April 25, 2024

- Key Technologies Shaping UX/UI in Web Portal Development - April 25, 2024

- Vue Component for Inline Text Editing: Enhancing Web Interfaces - April 25, 2024